High-Quality & Authentic Spanish Books

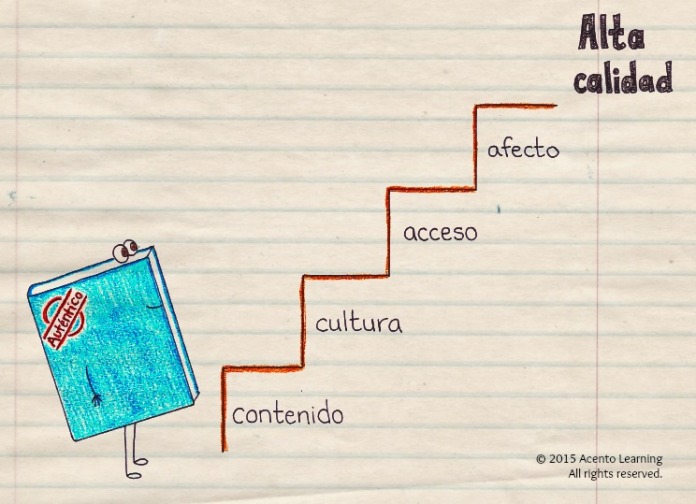

In our last blog entry, we defined what an authentic book in Spanish is and we offered some alternatives to find these books in the US. Now, an authentic book is not synonymous with a great book. Even though it’s wonderful that it was written in Spanish first, we still have to evaluate its quality and determine its place in our classrooms.

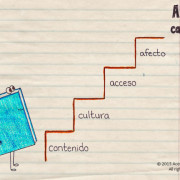

Some authentic books in Spanish are fantastic, necessary and unforgettable while others are… average. As teachers, we take a glance at a book and in less than a minute we have an almost visceral and assertive assessment about how good it is. However, the following questions can really help us fine tune our critical eye and determine what place we give to each book in our classroom and in our heart:

- It the book relevant to our content? Often our bookshelves resemble our closets! Just as we have lots of clothes on hangers and somehow “nothing to wear,” we also have lots of books and “nothing to read to our kids” relevant to the content we are teaching them. It’s such a success when we find an authentic book in Spanish that is at the heart of a teaching point.

- Is the language and message of the story aligned with my school’s social-emotional culture? Authentic books are like windows for our students to peek through and see the colors and flavors of hispanic cultures. However, there are some authentic books that can be considered “edgy” in our school contexts. Such as, for example, the Mexican bestseller La peor señora del mundo by Francisco Hinojosa. As a rule of thumb, if we are shocked by the content of a book or have doubts about its place in our classrooms, we should at least take it to our school’s administration and request their take/approval on the title.

- How much “front loading” should I employ for my students to access the vocabulary and/or context of this book? Some authentic books are extremely tied to their regional or local contexts, as is the case of La calle es libre or Imágenes de Barquisimeto; books that we can personally adore, but whose stories are born from local contexts. These types of books can have a place in our classrooms but they need to be very well contextualized for our students to gain significant meaning from them.

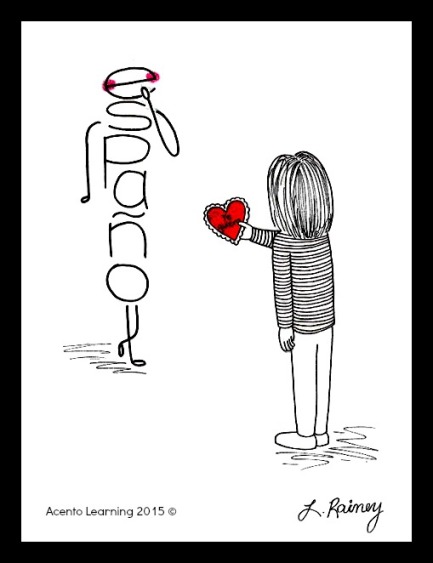

- And lastly, am I emotionally connected with this book? Even if a title passes the previous three questions, we may still not feel emotionally tied to it and write it off. In this case, remember that our kids’ reading tastes are diverse and it is possible that this title may still find its way into a student’s heart. On the other hand, if we love a book, we can work hard to find connections with our instruction. Reading a book that we love to our kids is magical!

As we can see, determining the quality of an authentic book and finding its ideal spot in our classrooms is hard work. That is why America Reads Spanish (ARS), an initiative aimed to increase the use and reading of our language in the US, is supporting this effort. In collaboration with Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruipérez – specialists in Hispanic literature – ARS has created an essential guide to Spanish reading for children and young adults. This list includes: the title, ISBN code, publishing house, reader’s age and summary of over 400 titles!

Here is the guide, enjoy!

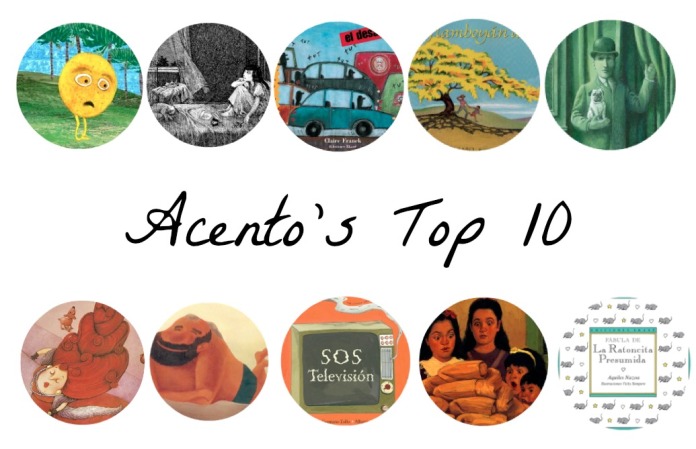

Lastly, we’d like to share some of OUR favorite authentic books in Spanish! These classics have accompanied us for years, elevating the status of Spanish in our primary classrooms and creating a strong Hispanic cultural connection.

In general, when evaluating an authentic book in Spanish, consider all you know about your students, the questions above and your educator’s gut. And remember, you already have an excellent critical eye! So tell us, what are your favorite authentic books in Spanish?!

Con cariño,